Six years ago I published “The New Moats: Why Systems of Intelligence are the next defensible business model.” In that blog, I postulated that startups would be able to build defensible moats using AI.

In light of all the developments in the past year, I want to revisit this framework and see what still holds true and what has changed.

I won’t rehash each and every technical breakthrough and changes in AI over the past six years. That has been well documented (or over-documented) in countless blogs, Tweet storms, and an infinite number of AI-generated avatars in my Instagram feed.

But I will, of course, point out that we wouldn’t be here without transformer models (first described in the Google Brain paper in 2017), which changed the game for language models. Progress went from gradual to rapid fire in the intervening years, and today’s AI landscape is, to borrow from a recent interview with my Greylock colleague (and Inflection AI cofounder and CEO) Mustafa Suleyman, “surreal.”

Large language models like GPT-4, PaLM2, and LlaMA are tangible examples of the way AI is becoming the enabling technology of this moment. I’ll point to essays written by my partners Saam Motamedi and Reid Hoffman, which dive into the current and potential impact of foundation models here and here.

Orienting oneself amid this Cambrian explosion of AI startups requires asking a basic question: Where is the enduring value in the market? Or, to ask myself a riff on the same question as six years ago: What are the new new moats?

To illustrate my thinking, I’ve taken a red pen to the original “Systems of Intelligence” framing, updating and amending predictions, posing new questions, and throwing out others. I hope this exercise helps to keep us grounded as we navigate the current AI hype cycle.

You can listen to a discussion of the key takeaways from this essay on the Greymatter podcast.

Why Systems of Intelligence™ are Still the Next Defensible Business Model

“In business, I look for economic castles protected by unbreachable ‘moats'”

To build a sustainable and profitable business, you need strong defensive moats around your company. This rings especially true today as we undergo one of the largest platform shifts in a generation as applications move to the cloud, are consumed on iPhones, Echoes, and Teslas, are built on open source, and are fueled by AI and data. These dramatic shifts are rendering some existing moats useless and leaving CEOs feeling like it’s almost impossible to build a defensible business.

In fact, open source AI models like LLaMA, Alpaca, Vicuna, RedPajama, etc, prompted the infamous leaked Google memo, “We have no moat, and neither does OpenAI.” The Google memo laments that the proprietary advantages held by Google and OpenAI are being disrupted by open source and, in particular, the release of Meta’s LLaMA mode which gave birth to an ecosystem developing (and improving upon) the seed that LLaMA has become. The memo concludes that “Paradoxically, the one clear winner in all of this is Meta. Because the leaked model was theirs, they have effectively garnered an entire planet’s worth of free labor.”

However, Meta isn’t the only beneficiary of this development. The entire market of startups, big and small, also have an advantage. In my original “New Moats” essay from six years ago, I was correct in pointing out the power of open source, but I was wrong to assume that it only favored the big cloud providers who could provide open source services at scale. On the contrary, this new generation of AI models can potentially shift power back to startups, as they can leverage foundation models – both open source and not – in their products.

In fact, some of the early beneficiaries of this new wave of AI are existing companies and startups that have been able to add generative AI into their applications like Adobe, Abnormal, Coda, Notion, Cresta, Instabase, Harvey, EvenUp, CaseText, and Fermat.

To paraphrase Darwin, “What is not the strongest (largest, most capitalized, or most well known) of companies that survives but the most adaptable to incorporating AI.”

In other words, this memo doesn’t so much pose a question of whether there are moats, but of where value accrues in the stack.

Historically, open source technology has reduced value in whichever layer it is available, and moved the value to adjacent layers. For example, an open source operating system like Linux or Android lessened the dependence of apps on Windows and iOS, and moved more of the value to the app layer. This doesn’t mean there is zero value in the open-sourced layer (Windows and iOS definitely capture value!). At the same time, you can still create value and attack Castles in the Cloud with open source business models, as we’ve seen achieved by the likes of Databricks, MongoDB, and Chronosphere.

In our blog six years ago we highlighted how the adjacent layer that benefited more often than not was the big cloud platforms. But, with respect to open source foundation models, we can see that some of the value that would have been captured by OpenAI or Google can now be shifted to apps and startups and infrastructure around the LLMs. OpenAI and Google can still capture value, and the ability to build and run these giant models at scale is still a moat. Building a developer community and network effects is still a moat, but the value captured by these moats is lessened in a world where open source alternatives exist.

In this post, I’ll review some of the traditional economic moats that technology companies typically leverage and how they are being disrupted. I believe that startups today need to build systems of intelligence™ — AI powered applications — “the new moats.”

Businesses can build several different moats and over time these moats can change. The following list is definitely not exhaustive and, fair warning, it will read like a bad b-school blog!

Traditional Economic Moats

Some of the greatest and most enduring technology companies are defended by powerful moats. For example, Microsoft, Google, and Facebook (now Meta) all have moats built on economies of scale and network effects.

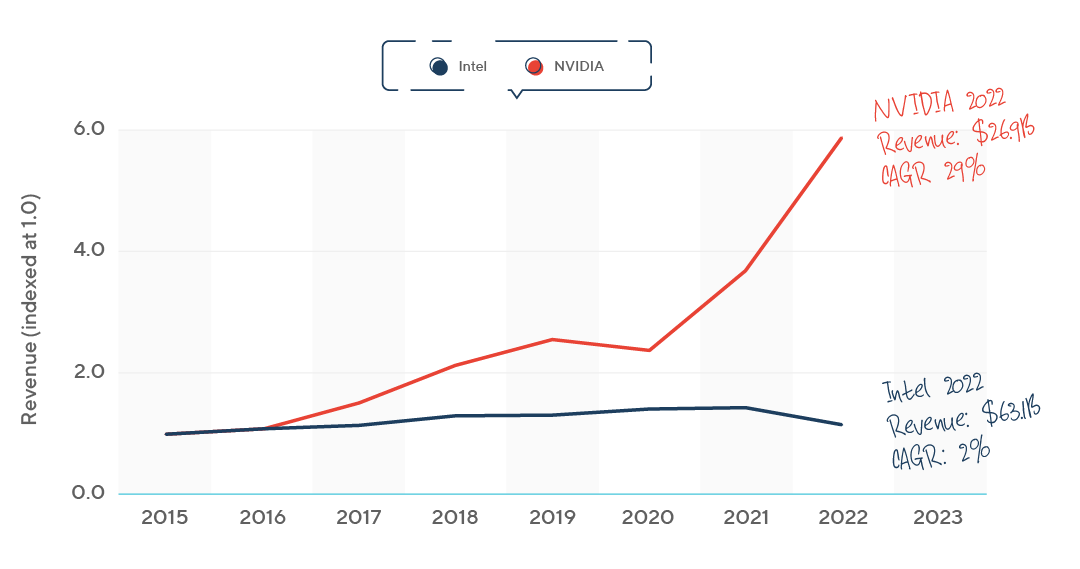

At this transitional moment of technology, the critical components to building worthwhile AI products are foundation models – which are trained on billions (trillions!) of parameters and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to train – and the computing resources needed to power them. If it were not for the release of LLaMA, I would imagine most of the value would accrue to companies like Google or startups like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Inflection that have access to capital (and GPUs) to train these models.One question ahead of us is the balance between models with trillions of parameters versus smaller models. If the race favors bigger and bigger models, then perhaps scale becomes the ultimate moat.

Economies of Scale: The bigger you are, the more operating leverage you have, which in turn lowers your costs. SaaS and cloud services can have strong economies of scale: you can scale your revenue and customer base while keeping the core engineering of your product relatively flat.

As vital computing partners to startups developing foundation models, the Big 3 cloud providers AWS, Microsoft, and Google are leveraging economies of scale and network effects to stay competitive in the current AI boom. Training AI models has become a data center scale problem combining compute and networking into a giant building scale supercomputer.

The reliance on large cloud providers to run complex machine-learning models has even led to a revival of Oracle as a go-to partner. The company initially lagged in the cloud server business, but made a series of smart moves with regards to AI primarily through its work with NVIDIA, which my partner Jason Risch described in an essay about AI’s impact on cloud. Oracle is currently working with a handful of leading startups including Adept, Character, and Cohere.

Network Effects: Best described by Metcalf’s law, your product or service has “network effects” if each additional user of your product accrues more value to every other user. Messaging apps like Slack and WhatsApp, and social networks like Facebook are good examples of strong network effects. Operating systems like iOS, Android, and Windows have strong network effects because as more customers use the OS, more applications are built on top of it.

One of the most successful cloud businesses, Amazon Web Services (AWS), has both the advantages of scale but also the power of network effects. More apps and services are built natively on AWS because “that’s where the customers and the data are.” In turn, the ecosystem of solutions attracts more customers and developers who build more apps that generate more data continuing the virtuous cycle while driving down Amazon’s cost through the advantages of scale.

First movers who gain traction can build network effects. OpenAI is rushing to build one of the first network effects moat around their models. In particular, their function calling and plugin architectures could turn OpenAI into the new “AI Cloud.” The race to build network effects is still too early to declare any company the winner. In fact, there are many players extending this notion to create agents like LlamaIndex, Langchain, AutoGPT, BabyAGI, and many others, all with the aim to automate parts of your app, infrastructure, or life.

Deep tech / IP / trade secrets: Proprietary software or methods is where most technology companies start. These trade secrets can include novel solutions to hard technical problems, new inventions, new processes, new techniques, and later, patents that protect the developed intellectual property (IP). Over time, a company’s IP may evolve from a specific engineering solution to accumulated operating knowledge or insight into a problem or process.

High Switching Costs: Once a customer is using your product, you want it to become as difficult as possible for them to switch to a competitor. You can build this stickiness through standardization, from a lack of substitutes, through integrations to other apps and data sources, or because you have built an entrenched and valuable workflow that your customers depend on. Any of these can act as a form of lock-in that will make it difficult for customers to leave.

Brand and Customer Loyalty: A strong brand can be a moat. With each positive interaction between your product and your customers, your brand advantage gets stronger over time, but brand strength can quickly evaporate if your customers lose trust in your product.

Old Moats Can Be Destroyed

Strong moats help companies survive through major platform shifts, but surviving should not be confused with thriving.

For example, high switching costs can partly account for why mainframes and “big iron” systems are still around after all these years. Legacy businesses with deep moats may not be the high growth vehicles of their prime, but they are still generating profits. Companies need to recognize and react when they are in the midst of an industry-wide transformation, lest they become victims of their own success.

Switching costs as a moat: X86 server revenue didn’t exceed mainframe and other “big iron” revenue until 2009.

Moreover, these massive platform shifts — like cloud and mobile — are technology tidal waves that create openings for new players and enable founders to build paths over and around existing moats.

Startup founders who succeed tend to execute a dual-pronged strategy: 1) Attack legacy player moats and 2) simultaneously build their own defensible moats that ride the new wave.

For example, Facebook had the most entrenched social network, but Instagram built a mobile-first photo app that rode the smartphone wave to a $1B acquisition. In the enterprise world, SaaS companies like Salesforce are disrupting on-premise software companies like Oracle. Now with the advent of cloud, AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud are creating a direct channel to the customer. These platform shifts can also change the buyer and end user. Within the enterprise, the buyer has moved from a central IT team to an office knowledge worker, to someone with an iPhone, to any developer with a GitHub account.

No More Moats?

In this current wave of disruption, is it still possible to build sustainable moats? For founders, it may feel like every advantage you build can be replicated by another team down the street, or at the very least, it feels like moats can only be built at massive scale. Open source tools and cloud have pushed power to the “new incumbents,” — the current generation of companies that are at massive scale, have strong distribution networks, high switching cost, and strong brands working for them. These are companies like Apple, Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Salesforce.

Why does it feel like there are “no more moats” to build? In an era of cloud and open source, deep technology attacking hard problems is becoming a shallower moat. The use of open source is making it harder to monetize technology advances while the use of cloud to deliver technology is moving defensibility to different parts of the product. Companies that focus too much on technology without putting it in context of a customer problem will be caught between a rock and a hard place — or as I like to say, “between open source and a cloud place.” For example, incumbent technologies like Oracle’s proprietary database are being attacked from open source alternatives like Hadoop and MongoDB, and in the cloud by Amazon Aurora and innovations like Google Spanner. On the other hand, companies that build great customer experiences may find defensibility through the workflow of their software.

I believe that deep technology moats aren’t completely gone, and defensible business models can still be built around IP. If you pick a place in the technology stack and become the absolute best of breed solution you can create a valuable company. However, this means picking a technical problem with few substitutes, that requires hard engineering, and needs operational knowledge to scale.

Foundation models are one of today’s deep tech/IP moats. The owners of the foundation models release APIs and plugins – while also continually working on even better products in-house. The relative ease at which developers can build on top of open source LLMs has led to an explosion of startups offering a range of products for specialized uses. But it’s already clear that most startups at this layer haven’t created a sufficient moat. Not only can they be accused of having “thin IP” (essentially, a simple app wrapper around ChatGPT), they also run the risk of facing direct competition from the foundation model provider, as we see playing out between OpenAI and Jasper.

There is potentially a world where big models address most of the complex problems, but smaller models solve specific problems or power applications at the edge like your phone, car, or smart home.

Today the market is favoring “full stack” companies, SaaS offerings that offer application logic, middleware, and databases combined. Technology is becoming an invisible component of a complete solution (e.g. “No one cares what database backs your favorite mobile app as long as your food is delivered on time!”). In the consumer world, Apple made the integrated or full stack experience popular with the iPhone which seamlessly integrated hardware with software. This integrated experience is coming to dominate enterprise software as well. Cloud and SaaS has made it possible to reach customers directly and in a cost-effective manner. As a result, customers are increasingly buying full stack technology in the form of SaaS applications instead of buying individual pieces of the tech stack and building their own apps. The emphasis on the whole application experience or the “top of the technology stack” is why I also evaluate companies through an additional framework, the stack of enterprise systems.

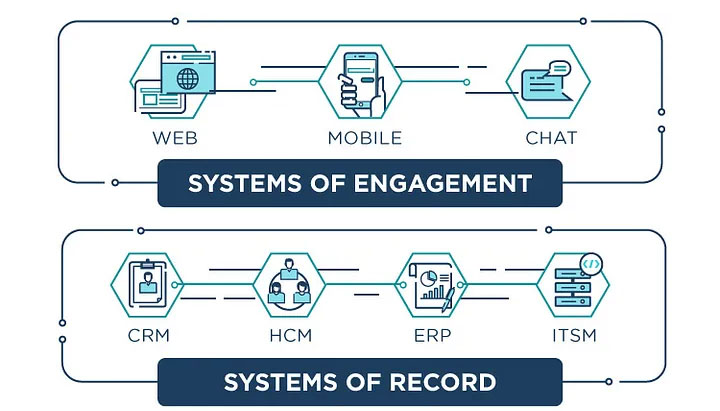

Systems of Record

At the bottom of the stack of systems, is usually a database on top of which an application is built. If the data and app power a critical business function, it becomes a “system of record.” There are three major systems of record in an enterprise: your customers, your employees, and your assets. CRM owns your customers, HCM, owns your employees, and ERP/Financials owns your assets. Generations of companies have been built around owning a system of record and every wave produced a new winner. In CRM we saw Salesforce replace Siebel as the system of record for customer data, and Workday replaces Oracle PeopleSoft for employee data. Workday has also expanded into financial data. Other applications can be built around a system of record but are usually not as valuable as the actual system of record. For example, marketing automation companies like Marketo and Responsys built big businesses around CRM, but never became as strategic or as valuable as Salesforce.

Systems of Engagement™

Systems of engagement™ are the interfaces between users and the systems of record, and can be powerful businesses because they control the end user interactions.

In the mainframe era, the systems of record and engagement were tied together when the mainframe and terminal were essentially the same product. The client/server wave ushered in a class of companies that tried to own your desktop, only to be disrupted by a generation of browser based companies, only to be succeeded by mobile first companies.

The current generation of companies vying to own the system of engagement include Slack, Amazon Alexa, and every other speech / text/ conversational UI startup. In China, WeChat has become a dominant system of engagement and is now a platform for everything from e-commerce to games.

If it sounds like systems of engagement™ turn over more than systems of record, it’s probably because they do. The successive generations of systems of engagement™ don’t necessarily disappear, but instead users keep adding new ways to interact with their applications. In a multi-channel world, owning the system of engagement is most valuable if you control most of the end-user engagement, or are a cross channel system that reaches users wherever they are.

Perhaps the most strategic advantage of being a system of engagement is that you can coexist with several systems of record and collect all the data that passes through your product. Over time, you can evolve your engagement position into an actual system of record using all the data you have accumulated.

Six years ago, I highlighted chat as a new system of engagement. Slack and Microsoft Teams attempted, but fell short, to become the primary system of engagement of the enterprise with a chat front-end for enterprise apps. This chat-first vision has not reached fruition yet, but LLMs could change that. Instead of opening an app like Uber or Instacart to order a car or deliver us groceries, we could ask our AI agent to order us dinner or plan a vacation. In a future where everyone has their own AI assistant, all engagement could feel like messaging apps. AI-based voice chat systems like Siri and Alexa will be replaced by intelligent chat systems like Pi, the personal intelligence agent developed by Inflection.ai

OpenAI’s plugin and function-calling announcements are building a new way to build and distribute apps, effectively making GPT a new platform. In this world, chat could become the front door to essentially everything, our daily system of engagement. It will be interesting to see how the user experience with AI applications evolves in the near future. While chat seems to be very popular today, we expect to see multimodal interaction models create new systems of engagement beyond just chat.

The New Moats: Systems of Intelligence™

I still believe that systems of Super intelligence™ are the new moats.

What is a system of intelligence and why is it so defensible?

What makes a system of intelligence valuable is that it typically crosses multiple datasets and multiple systems of record. One example is an application that combines web analytics with customer data and social data to predict end user behavior, churn, LTV, or just serve more timely content. You can build intelligence on a single data source or single system of record, but that position becomes harder to defend against the vendor that owns the data.

For a startup to thrive around incumbents like Oracle and SAP, you need to combine their data with other data sources (public or private) to create value for your customer. Incumbents will be advantaged on their own data. For example, Salesforce is building a system of intelligence, Einstein, starting with their own system of record, CRM.

In the six years since I postulated in the New Moats that startups would build systems of intelligence, we have seen several incredible AI applications like Tome, Notable Health, RunwayML, Glean, Synthesia, Fermat, and hundreds of more startups. While it’s still unclear where the lasting value will accrue in this emerging stack, this shift has provided ample opportunity for startups.

But as I alluded to earlier, we did not initially foresee the power of large language models, which have really increased the value of what we called systems of intelligence six years ago.

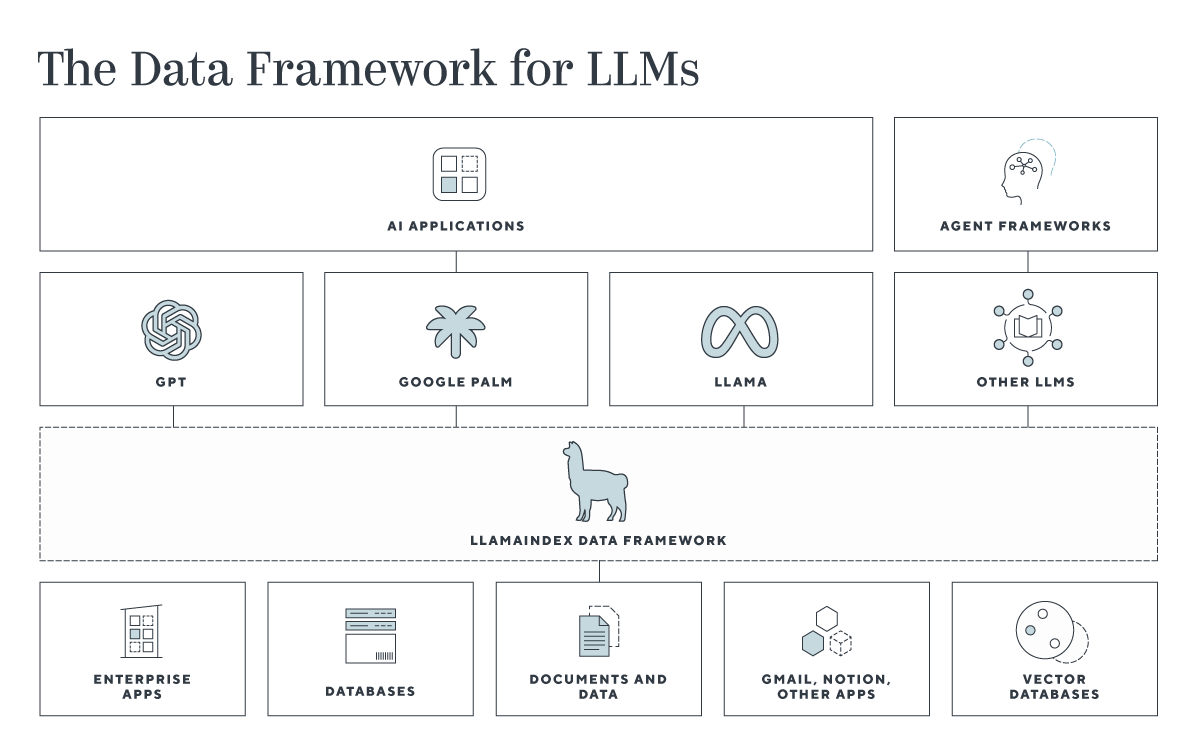

We are currently looking at the “new stack” required to build LLM apps. There has been a rush of new middleware tools to chain prompts or combine models as well as renewed interest in the use of vector embeddings for model memory. Just like we saw a spike in the number of companies founded to make cloud compute and storage more manageable, we’re seeing a cadre of startups designed to make foundation models easier to use.

We believe that this new middleware stack will include data frameworks like LlamaIndex to bridge enterprise data with LLMs, agent frameworks like Langchain to build apps and connect models together. In addition, there will be a new generation of security and observability tools required to ensure uptime and safety of these new applications.

As we illustrated a few weeks ago when we announced our investment in LlamaIndex:

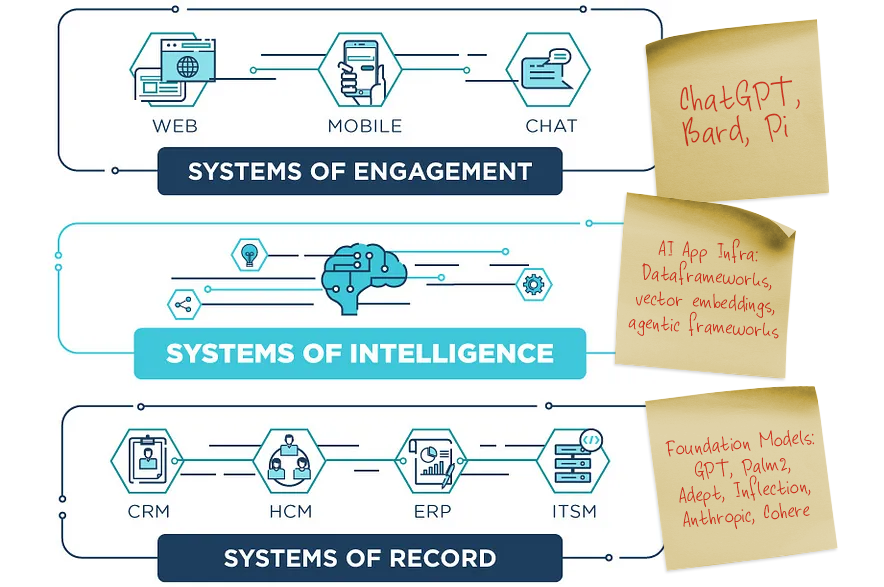

Or, to update the diagram in my 2017 essay:

The next generation of enterprise products will use different artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to build systems of intelligence™. It’s not just applications that will be transformed by AI, but also data center and infrastructure products. We can categorize three major areas where you can build systems of intelligence™: customer-facing applications around the customer journey, employee-facing applications like HCM, ITSM, Financials, or infrastructure systems like security, compute/ storage/ networking, and monitoring/ management. In addition to these broad horizontal-use cases, startups can also focus on a single industry or market and build a system of intelligence around data that is unique to a vertical like Veeva in life sciences, or Rhumbix in construction.

Previous generations of applications automated digital processes, but these new AI apps will risk replacing human processors – or, thinking of it in a positive way, they will amplify and augment human abilities and make individuals more productive.

AI tools already exist to make design work, coding, data processing, legal work, and other endeavors more accurate and faster. For example, in the legal vertical, companies like Harvey.AI and Even Up Law are performing the tasks of paralegals and associates. Github Co-pilot enables every developer to be orders of magnitude more productive, new developers can now code like a seasoned pro. Designers using Adobe’s new Firefly powered products can create digital images that previously took entire teams. Productivity applications like Tome, Coda, and Notion now enable each desk worker new super powers of speed and productivity. These are truly the AI-powered “Iron man suits” that were promised by technology. As we become more reliant on AI-powered applications, managing and monitoring trustworthy AI becomes even more important to ensure we aren’t making decisions based on a hallucination.

In all of these markets, the battle is moving from the old moats (the sources of the data), to the new moats (what you do with the data). Using a company’s data, you can upsell customers, automatically respond to support tickets, prevent employee attrition, and identify security anomalies. Products that use data specific to an industry (i.e. healthcare, financial services), or unique to a company (customer data, machine logs, etc.) to solve a strategic problem begin to look like a pretty deep moat, especially if you can replace or automate an entire enterprise workflow or create a new value-added workflow that was made possible by this intelligence.

Enterprise applications that established systems of record have always been powerful business models. Some of the most enduring app companies like Salesforce and SAP are all built on deep IP, benefit from economies of scale, and over time they accumulate more data and operating knowledge as they get deeper within a company’s workflow and business processes. However, even these incumbents are not immune to platform shifts as a new generation of companies attack their domains.

To be fair, we may be at risk of AI marketing fatigue, but all the hype reflects AI’s potential to change so many industries. One popular AI approach, machine learning (ML), can be combined with data, a business process, and an enterprise workflow to create the context to build a system of intelligence. Google was an early pioneer of applying ML to a process and workflow: they collected more data on every user and applied machine learning to serve up more timely ads within the workflow of a web search. There are other evolving AI techniques like neural networks that will continue to change what we can expect from these future applications.

These AI-driven systems of intelligence™ present a huge opportunity for new startups. Successful companies here can build a virtuous cycle of data, because the more data you generate and train on with your product, the better your models become and the better your product becomes. Ultimately, the product becomes tailored for each customer, which creates another moat – high switching costs. It is also possible to build a company that combines systems of engagement™ with intelligence or even all three layers of the enterprise stack but a system of intelligence or engagement can be the best insertion point for a startup against an incumbent. Building a system of engagement or intelligence is not a trivial task and will require deep technology, especially at speed and scale. In particular, technologies that can facilitate an intelligence layer across multiple data sources will be essential.

Again, we’re already seeing the virtuous cycle of data play out. Not only on the value of data for training the original model, but the value of user data, feedback loops on models and apps, and (in the extreme case) RLHF all compound over time to deepen the data moat.

There is clear potential for ChatGPT or personal AI tools like Inflection AI’s Pi to serve as the primary channel to every task, be it accessing apps, developing software, or communicating in a range of scenarios. In addition, data frameworks like LlamaIndex will be key to connecting your personal data with LLMs. The combination of models, usage data, and personal data will create personalized application experiences for each user or company.

Finally, there are some businesses that can build data network effects by using customer and market data to train and improve models that make the product better for all customers, which spins the flywheel of intelligence faster.

In summary, you can build a defensible business model as a system of engagement, intelligence, or record, but with the advent of AI, intelligent applications will be the fountain of the next generation of great software companies because they will be the new moats.

The New Moats are just the Old Moats.

While the rise of AI is exciting, in many ways we have come full circle in our quest to build new moats. It turns out that the old moats matter more than ever. If the Google “We have no moats” prediction is true and AI models enable any developer with access to GPT or LLaMA to build systems of intelligence, then how do we build a sustainable business? The value of the application is how to deliver the value. Workflows, integration with data and other applications, brand/trust, network effects, scale and cost efficiency all become drivers of economic value and the creator of moats. Companies that are able to build systems of intelligence will still need to master go-to-market. They’ll have to perfect not just product-market-fit, but product go to market fit.

AI doesn’t change how startups market, sell, or partner. AI reminds us that despite the technology underpinning each generation of technology, the fundamentals of business building remain the same.

The new moats are the old moats.

Thanks to Saam Motamedi, Reid Hoffman, Mustafa Suleyman, Jason Risch, Corinne Riley, Heather Mack, Elisa Schreiber, and the rest of my partners at Greylock for their input. This post was also helped through conversations with my friends at several Greylock-backed companies including Adept, Inflection, Instabase, LlamaIndex, Truera, Notable Health, and dozens of founders and CEOs that have influenced my thinking. Thanks to Eli Collins who inspired the original essay six years ago. All good ideas are shamelessly stolen and all bad ideas are mine alone.

Title inspired by The New New Thing by Michael Lewis.